Flow Facilitator Spotlight: Creativity and Pattern Recognition

- Wynne

- Nov 27, 2025

- 5 min read

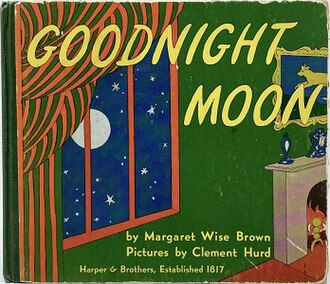

The Genius of Margaret Wise Brown's Goodnight Moon.

This is the fourth in a series exploring the 21 +/- conditions that researchers have identified as helping to facilitate a state of flow. The list of conditions is certainly not exhaustive! I'd love to hear from you if you've found other ways to set yourself up for optimal experiences - please share your thoughts in the comments!

Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon was not a staple of my childhood. I don’t ever remember seeing it or even hearing about it until we were gifted a board book-style copy when our kids were small. And I have to admit, I didn’t love it; I thought it was sort of lame. The stories I liked reading to the kids (Jez Alborough’s Hug, Olivier Dunrea’s Gossie, for example) were cute and engaging and told a satisfying little story that we all liked to read again and again. Goodnight Moon, on the other hand, never really went anywhere, and the illustrations (by Clement Hurd) seemed old-fashioned to me (I mean, duh - it was originally published in 1947!). The kids, however, loved it. They liked pointing out all the little things they were saying good night to, they loved searching for the kittens and the mice, they loved the gentle melody of the rhymes. Turns out, pedagogically speaking, they were right and I was wrong (this would not be the first time, nor was it the last).

Brown herself was not just an author of children’s books, but was first a teacher at New York City’s Bank Street Experimental School, a progressive, “early laboratory school” staffed by teachers, psychologists, and researchers who aimed to improve early childhood education through an emphasis on children’s social, emotional, and cognitive development.

“Brown’s writing style was heavily influenced by her teaching work, and she sought to write children’s books that mirrored the way young children experienced the world around them. That meant simple language, along with stories and concepts that were easy to follow and understand.”

Turns out, young children don't crave plot. They don't need story arcs. They are drawn to patterns, to rhythms. They crave the opportunity to explore, to point, to search and discover. In other words, they gravitate patters - the building blocks of creativity.

Why Patterns Matter for Creativity

In our last Forge & Flow newsletter, we explored novelty, and the spark that comes from encountering something new. Where novelty is the quality of being new or unusual, creativity is the process of producing something new and useful. Novelty is a component of creativity, but not all novel things are creative. Creativity is often defined by originality, imagination, and the ability to bend or reinterpret existing rules. But originality rarely comes from nowhere. Instead, creativity typically arises when the brain recognizes patterns — connections, structures, relationships — and recombines them in a fresh way. Pattern recognition provides order in what might seem like chaos, helping us link disparate ideas and turn them into something meaningful.

Children do this instinctively through exploration, which research shows is a vital component of creativity. Their play is essentially pattern hunting: noticing, testing, rearranging, and discovering. Goodnight Moon works so well because it facilitates this process: it offers a room full of patterns to notice, revisit, and reassemble each night.

Divergent Thinking: The Playground of Creativity

A key engine behind creativity is divergent thinking — the spontaneous, free-flowing generation of many possible ideas. Unlike convergent thinking, which funnels toward a single correct answer, divergent thinking loves quantity, surprise, and the nonlinear. This wide-open mode is where novel ideas begin.

It’s also where creative flow tends to emerge.

Creative Flow is a Different Kind of Flow

Flow is usually associated with clear goals, immediate feedback, and a strong sense of control, qualities seen in sports, gaming, or highly structured skill-based tasks. But creative flow doesn’t work that way. Artists and creators often step into uncertainty rather than clarity. Goals are fuzzy. Feedback is ambiguous. And control? It often takes a back seat to discovery. But creativity naturally invites flow, because it engages the mind in a way that is both absorbing and challenging. When creativity acts as a flow facilitator, it typically involves:

Exploration Over Execution

Creative flow begins with curiosity. The creator explores -- testing possibilities, playing with materials, trying out connections. This openness removes pressure and invites a sense of “let’s see what happens,” which lowers self-consciousness and accelerates immersion.

Transient Hypofrontality: The Inner Critic Quiets Down

During creative flow, the brain reduces activity in regions linked to self-monitoring, judgment, and doubt. This temporary downshift -- called transient hypofrontality -- helps ideas emerge more freely. Without the inner critic’s constant commentary, associative thinking becomes easier, and surprise becomes possible.

The Fusion of Thought and Action

In creative flow, a musician is not thinking about the piano -- they are at the piano, playing the music before conscious thought catches up. A painter doesn’t think through each brushstroke; the brushstroke simply happens. Csikszentmihalyi described this as idea and action becoming fused, a hallmark of creative flow that sets it apart from more "traditional" flow states.

Emotional Meaning-Making

Creativity is not just cognitive; it is deeply emotional. Ideas carry resonance. Colours carry feeling. Stories carry significance. This dimension of meaning-making enables the effortless attention and joy characteristic of flow.

The Perfect Balance of Challenge and Skill

Even in ambiguity, creative work requires skill: the ability to write a sentence, mix a colour, shape a melody, think outside the box. Creative flow emerges when the challenge of exploration meets the skills already present. It feels both stable and stimulating at the same time.

How Creativity Interacts with Other Flow Facilitators

As with almost all the flow facilitators, there is a lot of overlap and interaction with the other factors that can help move us into flow. None of them exist in isolation. For example:

Novelty fuels creative excitement

Pattern recognition supplies the raw materials for inventive connections

Meaning-making gives direction to ideas

Embodiment (actually having your hands on the piano keys, in the clay, or at the keyboard) anchors attention

Because of this, creativity is a particularly integrative flow facilitator: it gathers many other facilitators together for a unique and rewarding flow experience by welcoming uncertainty, experimentation, the possibility of surprise, and leaps of insight.

Children Are Experts in Creative Flow

Kids experience creative flow regularly. Their play is a blend of exploration, pattern discovery, imagination, and meaning-making. They tend to have fewer inhibitions, less self-consciousness, and a much quieter inner critic -- all ideal conditions for creative flow.

This is precisely why Goodnight Moon, with its simple patterns and imagery works so well for kids. It invites the kind of gentle, exploratory engagement that fuels creativity and flow.

Creativity as a Life-Wide Flow Facilitator

As a not-particularly artistic person, creativity is thankfully not limited to the arts. It can enhance flow in:

problem-solving

relationship-building

strategic thinking

leadership

learning

and everyday decision-making

Anywhere we generate new ideas or connect patterns, creativity is active, and flow becomes more accessible for anyone willing to explore.

____________________

REFERENCES:

Doyle, C. L. (2017). Creative flow as a unique cognitive process. Frontiers In Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01348

Evans, N. S., Todaro, R. D., Schlesinger, M. A., Michnick Golinkoff, R., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2021).

Examining the impact of children’s exploration behaviors on creativity. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Volume 207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105091.

Comments